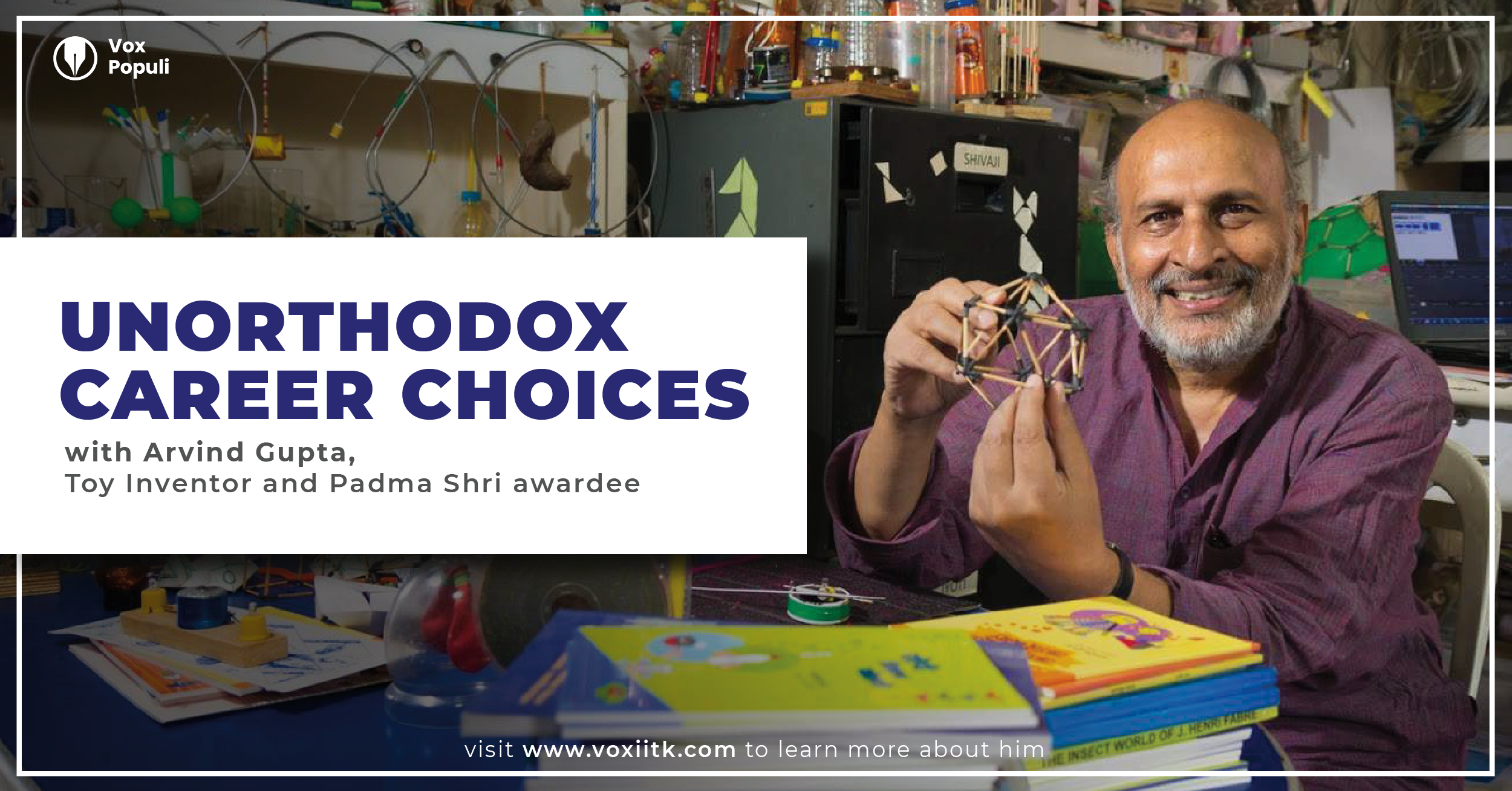

Vox Populi brings you the fifth edition of the series Unorthodox Career Choices. We interview people who have taken the leap of faith and bring their stories to you. This edition brings you the story of Arvind Gupta, an alumnus who graduated from the 1975 batch. He is a Toy inventor, a Teacher and a Padma Shree awardee. He was an engineer at TELCO, who left his job to teach science to children from tribal villages. He developed many useful low-cost toys from trash. The possibilities of using ordinary things for doing science and recycling modern junk into joyous products appealed immensely to children. Check out some excerpts from our conversation with Arvind.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Tell us about your story. How and when did you decide that this is what you really want to do? How did you get interested in the art of toy-making? Who are the people that inspired you in the beginning? And what was your motivation?

I did B.Tech in Electrical engineering from IIT Kanpur (1970-75). Those were turbulent political days. In 1968 students of Paris were out on the streets challenging authority. The Naxal and the JP movements were in full swing in India. Whenever there is a political churning of society it unleashes a lot of social energy. For instance, during the National Movements, thousands of professionals chucked their jobs and joined Gandhiji. In IIT Kanpur a bunch of students formed SAHYOG – an organisation to help teach the children of the mess servants. For 5 years I taught at the Opportunity School. The nicest thing about IIT Kanpur was the exposure to a wide range of cultural activities and extramural lectures. In 1972 Prof. Anil Sadgopal, a Ph.D. from Caltech had left his job in the TIFR and started a science teaching program for village children in Madhya Pradesh. In his talk, he mentioned that we all have a very romantic image of village India – green fields, gaon ka panghta, etc. But once you go to a village, problems of class, caste and gender hit you squarely in the face. This quizzed me. Many people in my time wanted to do something meaningful – something which would help our people. This was the defining political slogan of those days – “Go to the people, live with them, love them, start from what they know, build on what they have.”

Considering that you had a secure and prosperous career ahead at TELCO, how did you cross the mental threshold of giving it all up and joining an underpaying village school program? How did your family react to this?

In 1975 I got a job in TELCO (Tata Motors) as a GET. The two-year training on the shop floor was amazing. But after the regular placement, the job became boring. So in 1978, I took a year’s leave from my job and worked with the Hoshangabad Science Teaching Program (HSTP) and with the famous architect Laurie Baker. The HSTP was a pioneering program started by Dr. Anil Sadgopal to make science fun for village children by designing low-cost, affordable teaching aids using local materials. In the very first month, I designed the Matchstick Mecanno – which uses bits of cycle valve tubes as joints and matchsticks to build structures. I loved that kind of work as it would help many children. Later my first book Matchstick Models & Other Science Experiments was translated and published in 12 Indian languages and also in Chinese.

My parents had never seen the inside of a school. So, they didn’t have any great expectations from me – getting a multi-national job or going to the USA. I was very lucky to be free from family pressures. I could chart my own journey. In 1980, when I finally quit TELCO, my mother said to me, “Good, that you left the job. Now you will do something meaningful.”

Tell us about your days at IIT Kanpur. How did those four years influence your outlook? What role did IITK play in your unconventional career choice?

Back then there was a 5 year BTech program with a strong emphasis on Social Sciences. My AIR was 218. So I got Electrical Engineering, which had all the toppers. I learned so much from my clever peers. We had some great teachers – Prof. CNR Rao, Prof. D. Balasubramanian. We had an amazing English teacher, Mrs. Suzie Tharu. I did a lot of tinkering with my friend Akhilesh Agarwal. We made aero-models, a compressed air engine, a go-kart, and a See-saw for the Opportunity School. In 5 years we saw every good film by Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, Bergman Ritwik Ghatak and Fellini, heard Begum Akhtar and Pandit Ravi Shankar alive. The hallmark of a great institute is that it slowly shapes and tones your sensibilities. Without telling you it gets under your skin. For someone coming from a small town of Bareilly in UP, IIT Kanpur opened up an entirely new world. It opened up my mind to amazing possibilities.

Tell us about a regular day in your life now.

For most of my life, I worked as a freelancer – got fellowships to write books, presented over 125 science videos for the Doordarshan program “Tarang”, conducted workshops in over 3000 schools in 25 countries, wrote books and translated over 700 books in Hindi. For 11 years I worked in the Children’s Science Centre of IUCAA, Pune.

Now I am semi-retired. For many years I was on the advisory board of the National Book Trust and saw the poverty of children’s books in Hindi. Every day I translate children’s books in Hindi. They all go on the internet archive. We have translated some of the world’s best award-winning children’s books into Hindi.

You have published quite a few books, have a well-established YouTube channel and also, an active site. Do you have a team working with you? How do you manage all this?

I spent 14 years in New Delhi. For the first six years, I taught in a small school run by the Aurobindo Ashram called Mirambika. In 2003 we shifted back to Pune. I was invited to work in the children’s science center of IUCAA (Inter-University Centre for Astronomy & Astrophysics) by Prof. Jayant Narlikar. We were a team of 3 highly motivated people. Every day we made a short 2-minute video on “Toys from Trash”. Today we have 8700 videos on Youtube with a viewership of over a 100-million. We scanned over ten thousand books on education, environment, science, math, children’s books, etc and put them on the web. Every day 12 to 15 thousand books are downloaded from my website. It just shows the hunger for good books in our people. Across the world, any creative and useful work is usually done by small focussed and dedicated teams. I was singularly lucky to be a part of such a team.

Since you are involved in public service full-time and all your toys and books are available for free, how do you earn your livelihood? Do you have a family that is financially dependent on you?

Many schools that invited me to do a workshop paid me some honorarium. I never had a fee. I accepted whatever was offered. Some schools that needed me the most could not pay, but that was fine with me. I never sold anything. I designed to help the poor. All my work is free for all.

Inspired by Gandhi, I live a simple life with few needs. Often people talk about Life Insurance. I jokingly talk about Wife Insurance! My wife worked in a college and earned enough for the family.

Share with us your experience of working in villages, remote places, municipal schools for over 40 years. What kind of social impact have you been able to make so far?

I have been privileged to work in some very poor schools both in cities and far-flung villages. First I show children a few toys. They are made of old plastic bottles, newspaper caps, pumps which can inflate a balloon or throw water 15-feet away, or a simple electric motor. After seeing these toys I can see a twinkle in their eyes, a smile on their faces. There is great hope for our children. In their eyes lies our future dreams. We need to invest heavily in them.

All my Science Activity books are just a click away.

Arvind Gupta’s 25 Science Books ENGLISH Google Drive – AG-25-ENG

Arvind Gupta’s 20 BOOKS (HINDI) Google Drive – AG-20-HINDI

What hardships did you face to scale up your teaching methodology and how did you overcome those hardships?

The best thing that I did in 2003 was to set up a website – www.arvindguptatoys.com. I am quite technologically challenged. At each stage, kindred and tech-savvy friends helped me. One of my friends showed us how to make videos using an ordinary digital camera. That was in 2006. We made 1100 videos in English. Each video was 2-minutes, short, crisp and catchy. We collaborated with like-minded friends across the country to dub them in a dozen Indian languages. We have over 300 videos in Spanish. They have been viewed by millions across 26 countries that speak Spanish.

The educational terrain in our country is very barren. It is rocky and full of stones. There is no soil. Even a good seed will wilt for lack of soil. Every day we try to make a fistful of soil – make educational classics like Divaswapna, Tottochan, Teacher, Summerhill, How Children Fail, Sudbury Valley School, etc. available to our teachers in many-many Indian languages. We have inched forward but much still remains unfinished.

How do you think the Indian education system has evolved over the years from a scientific point of view? And what needs to change in the future?

Forty years back there was only rote learning. There has been a shift from chalk and talk to “project-based” methods and “activity-based” learning. Now there are few thousand Atal Tinkering Labs. This is a welcome shift.

Our educational system is inherently based on inequality. Depending on your position in society, your economic class, you have different schools. International schools with IB for the super-elite. Kendriya Vidyalayas for the organized central government employees. Navodaya Vidyalayas for the emerging rural elite. Some excellent private schools for the rich. The middle class has no stake in government schools anymore. They have long lost trust in them. The poor have no choice but to send their children to government and municipal schools – which are in poor shape. In recent years the Delhi government has shown a practical way to improve our government schools. All states must learn from it.

There is a tremendous scarcity of good educational material on the internet in our regional languages. There is a plethora of good material in English, but very little in our vernacular languages. We must translate the best resources in the world into our regional languages. TED talks represent the very best. They are inspiring and free. Has any state government, SCERT, DIET, or any NGO dubbed any TED talks into Hindi, Tamil or Gujarati?

You have won various international and national awards, including the Padma Shree. What is your plan ahead? And is there something you are working on nowadays?

I am largely confined at home now. With the COVID-19 lockdown, I have done a few webinars. I also make short videos in English and Hindi introducing classic books on education to teachers. Hopefully, these short videos will motivate teachers to read these books. I have an abiding interest in children’s picture books. I keep translating them – one book one day. It has been a good life and I have enjoyed every bit of it.

What message would you like to give to the IITK community?

It is a privilege to be in IITK. We must use this opportunity to help our people – especially the poor. Dream big and live your dream – life is too short to live the stale dreams of others.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Credits- Abhimanyu Sethia, Ananya Gupta, Devansh Parmar, Raj Varshith Moora, Sarvesh Bajaj, Varun Soni