Vox brings to you a conversation with Orijit Sen who visited IITK for a comic workshop. He is the co-founder of People Tree, an extraordinary artist, storyteller, activist, social documentarian and India’s first graphic novelist. From creating comics to editing anthologies, from teaching to writing, he has been an active and influential figure in the comics scene in India. Orijit conceptualized – and led a team that executed – one of the world’s largest hand-painted murals, installed at the Virasat-e-Khalsa museum. His work has been widely published, exhibited, and awarded within India as well as internationally.

——————————————————————————————————————

Vox: How did you end up choosing art as a career path?

Orijit: I became quite serious about becoming an artist sometime around high school. It was a bit of a struggle against my parents, teachers, and others. When he was young, my elder brother was rebellious and inspired me a lot.

Back then, the only choices were becoming a doctor, an engineer, or a lawyer. The other options didn’t even exist. When I tried to tell my parents I wanted to be an artist, they were aghast. My parents tried to convince me to be a doctor, but eventually, I announced I would not. I want to be an artist. I remember they were seriously worried. I was among the top five six students in my class. As long as I kept showing reasonable academic results, it would be much harder for me to become an artist. So I deliberately started failing my exams, to a point where my parents were driven to so much despair that they agreed.

When I look back now, it’s funny, but I wonder at that age what gave me the self-belief to say, no, I will do this only while everybody is telling me from every side that you will be struggling in life. It will be miserable, and you won’t make money. I was like yeah, I get it, but that’s fine. That’s part of being an artist. You have to struggle.

Vox- In the 1990s, you published graphic novels. Why did you choose that medium when no other artist in India was using it? Why did you shift to platforms such as Instagram and a more digital art form?

Orijit: I’ve always been fascinated by comics. I used to draw comics as a kid too. I was always told that this is not a serious artist’s medium. Making comics one step worse, like you’re wasting your time making comics. But I was always really drawn to it and convinced of the medium’s power. I remember I went to the library in the college once. I had access to amazing comics from all over the world, including comics based on politics, adult comics, etc. That is how I knew it was a medium. Back then, there was no internet, and as a kid growing up in India, you had no access to information from anywhere else. You only had what you had around you.

We used to read Phantom, Andre, Individual, and all these things. Tintin was a big influence on me as a kid. It used to make me feel like I was entering into the world with Tintin. So I was very inspired to draw comics.

In 1984, Art Spiegelman’s Maus went on to win the AZA Prize. It was featured on the cover of Time Magazine, and it was yet another one of my inspirations! Like- This is what I’m talking about!

Vox – How did you first start making memes and satirical posters on digital media?

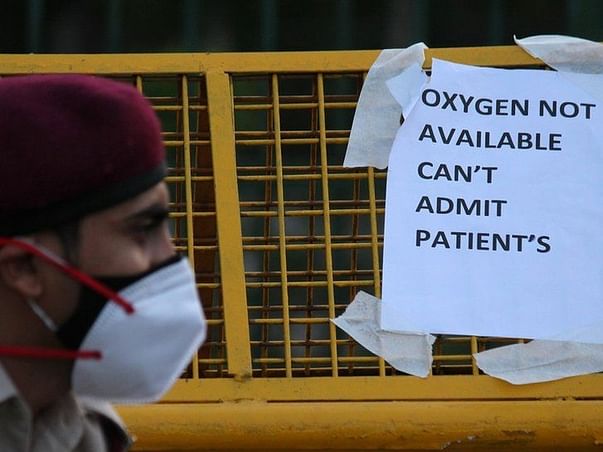

Orijit: In 2010, Binayak Sen was arrested by the Chhattisgarh government, and I was part of a campaign demanding his release. I made a poster about it and posted it on Facebook. That’s probably the first time I used this kind of art. I just posted it in the evening, and I fell asleep. In the morning, I woke up, and there were so many messages and comments from Facebook! It was fascinating! Then two days later, I saw that people protesting in Chhattisgarh, Raipur, had printed out that image and were marching with that poster as a kind of image for which they had taken into their march. That’s when I realized that this is a very powerful tool.

I also liked the fact that nobody needed anybody’s permission. I just posted on Facebook. They took it from there, made blackouts, and started marching. The fact that one night I was sitting in Delhi talking about Binayak Sen and suddenly became part of the landscape of the protest in Raipur. I’d never experienced anything like that! That’s when I realized the power of this whole thing. So I started doing more such work.

Vox: How do you describe your art style? How would you characterize your art style?

Orijit: This question is particularly interesting because I don’t feel like I’m following any style. I’m just drawing the way I feel like drawing. Many people have told me that they can recognize my style when they see it, but this is not something I’ve done consciously or ever done consciously. I just draw what I want to draw with whatever tools at hand.

Vox: Is there a process to making art? What goes into your head when you are sort of creating an art piece in terms of ideation, planning, and execution of it?

Orijit: I do many different kinds of work, for example, big murals and large artworks, comics, and graphic novels. In addition to that, I do these one-off memes and satire about what’s going on in the country. Those are the ones that I am most known for because that’s what goes out on social media and reaches the masses. The process for making each of these kinds of work is different.

I like to do a lot of visual research. We are such a textual society that all our ways of recording our histories are that we write them. Lately, photography and video have become possible, and people use it a lot. We associate photography and video with on-the-spot current events kind of reportage, but I use it in a longer reflective way to show imagery and visuals to tell stories which I feel are very important. So for me, usually when I start on a longer project, I do spend months, sometimes more than even a year, just researching my subject visually.

I focus on the essence of the scene because I’m not going to be drawing every detail, you know! I’ll look at your body language, I look at the way you express yourself through your clothes or your posture. These things, to me, are a more essential viewing of things. I look at it, and I internalize it. For example, let’s say I want to do a mural in Punjab. So I visit Punjab, start meeting people, and start drawing things, and those things become internalized. I take photographs, but more importantly, I always draw. Even though it’s quick sketches, it becomes part of my mental, visual vocabulary for creating the work.

With social media pieces, it’s different. If I feel a lot of anger or pain about something that’s happening around, I make relevant artwork to channelize those feelings. I take around half an hour to produce a meme. Once I have an idea or I’ve read something that’s inciting strong emotions, I need to deal with it, and my way of dealing with this is by creating a meme that I can share with others. I give myself a very short deadline to do that, it’s very instantaneous in a way, and there’s a logic to that. The creation of it is instantaneous, the absorption is also instantaneous. You know, it spreads immediately, and people see it.

Vox- A related question is that when when you have commissioned art, how do you sort of balance between giving in to, say, your client’s requirements and artistic integrity?

Orijit: It depends. Some clients have more specific things, like the Punjab mural was done for the government, right? I have to be subversive in criticizing the government. I do it but in a very subversive way because my work is always very sprawling with a lot of detail, so you can hide a lot of things there. The people in charge, who are representing the government, are usually some bureaucrats or somebody appointed. They don’t necessarily usually know too much about art, nor are they interested, they’re just supposed to do their job. So you can slip in a lot of things, a lot of things by which they don’t realize what’s going on. It can look like a nice scene, but when you look a bit deeper, there are all kinds of other things being shown in that scene. That’s what I usually do. I try to slip things and subvert the idea that is being presented. At one level, it seems to be about a happy picture of Punjab with progress and technology and all that, but if you look a little closer, you see there are a lot of other things going on which are actually contradicting this narrative of peaceful, happy Punjab.

Vox – Is it important to you that your art is recognized by your name?

Orijit: One of the good things about social media is that it helped me engage with an audience. Suppose my work gets published in a magazine or a book or it gets shown in a gallery. First of all, there’s very little opportunity for direct interaction with my audience. They may come and see it, and they may like it or not like it, or they may have opinions.

But on social media, there are immediate reactions. People say things, critical things, and I value that. I value the fact that social media gives me this chance to interact with my audience and for me to get feedback from people. So I don’t want it to be anonymous. I do want my work to be associated with me because it’s essential for a kind of conversation to happen.

Vox: What did you think of the financial aspect of your career when you decided to pursue art?

Orijit: I was aware that I would’ve to sacrifice to be an artist. I was prepared for it. Of course, as a kid, you don’t know what sacrifice really means, right? You don’t know what it really means to be broke to live without a job. But at least in my imagination, I had accepted that my life could be one of these.

Initially, it was up and down. I’ve had long periods of being very broke. I did regret it at one point after I made River of Stories. I spent three years doing this, and nobody was interested in it when it came out. Nobody knew what it was. There was no reaction. There was no response. I thought to myself that I was going to be hailed as this great artist, but nothing, nobody cared. At that time, I felt quite disheartened. Moreover, this was the same year my daughter was born, and suddenly I felt like, what am I doing- I’m living this sort of fantasy life, and how am I gonna bring up my family? How am I going to pay for my daughter’s education? So for a couple of years, I stopped making comics and started to do commercial projects. But that didn’t last very long. I went back to making comics soon enough. When we first moved to Goa, we were broke a lot of the time. Fortunately, in my daughter’s school, the fee was 15 rupees a month. Even for those 15 rupees, we had to go to the bank, make a demand draft for 15 rupees, and pay the school.

It has been up and down, but all in all, I would never replace the life I have had for something else. If I look at the struggle that people, who didn’t choose that hardship, have to go through, they have to live within this world without any agency. At least whatever hardship I have been through, I’ve chosen. It has been up and down, and it went down, and then I came up. But you know, for a lot of people in that world, that option is not even there.

Vox: How many countries have you been to, and can you tell us some of your experiences in those countries? How does community art differ across the places you have been to? What is the importance of art apart from recreational purposes?

Orijit: Ah! I have lots of interesting stories because normally when you travel, you end up meeting interesting people – especially when you are traveling as an artist, you are meeting other artists. My trip to Palestine definitely stands out in my memory. It was like traveling and meeting people who are not necessarily artists in a self-described way but who use art as part of their struggle. For example, the scene of painting murals. A lot of the West Bank area in Palestine has, over time, been quite destroyed by attacks. So there are a lot of either broken buildings or uninherited architecture, and people use those walls to create artwork. What excited me in Palestine was that there is no professional art scene or galleries. People are using these public walls and spaces to create art.

Even during the Shaheen Bagh Protests, art was created publicly in the places where people were gathered, like on the walls. When there is a situation where people are struggling and fighting for their rights somehow, art comes to the forefront. Also, in such times we realize how important art is for us, for our identity, our expression for freedom – of being able to express what we feel. When there is a very organized, peaceful society, then eventually, art resigns to the periphery, like gallery spaces, and becomes secondary. It perhaps becomes not necessary but something that you enjoy, it becomes a form of entertainment.

Although I do show my work in galleries from time to time, to me, that is not the primary place for art. We create the artificial spaces in which we are supposed to go and view art, performances, theatre or music. We always create these confined and well-controlled, sanitized kinds of spaces to engage with art. To me, that is actually not what is the most exciting or powerful aspect of art, the art that gets separated from the mainstream life of society. You know, as an artist or performer, you do want to have the best of conditions in which to show your art like audio, lighting etc. But in that process of showing off your art at its best, you are taking it away from the mainstream of society. So I am always trying to work with forms of art that allow me to reach out to people.

When I travel, I always seek out art and artists who are working in the public domain rather than in privatized spaces. That was one of the things that really moved me about my time in Palestine. I was just talking to a professor of Japanese languages. We were chatting about the various things that I’ve seen in Japan in terms of art.

Although it’s not like that much in the public domain, there’s something strong about art in Japanese culture because of the media. I was fascinated by the manga culture of Japan. And it’s not in the public domain, but it reaches into the public sphere because of the popularity of the medium. When I travel in the Delhi metro, for instance, 99% of people are on their phones. In Japan, I was amazed that people are reading manga. That’s their form of getting immersed into something, and there is manga for every kind of person. There are so many varieties of manga, and everybody has their own kind of connection.

Vox: Coming back to India specifically when you released provocative art like, say, Vadnagar man or Punjaban – did you fear any backlash when creating or publishing it? And also, how do you deal with it? And then the light question is, is there some element of self-censorship that creeps in?

Orijit: Yeah, so I do feel quite afraid when I post some of this stuff. The thing is that in most situations, let’s say before social media, I was doing work that was critical of the government and authorities. Before that, if you were critical of the government or the authorities, there would be a certain level of, let’s say, disapproval. But I don’t recall feeling afraid at any point back then.

Now I do. It does come to my mind every other day, and I do feel afraid, but I have to overcome that because that is exactly what you’re talking about. Self-censorship is something that is, on the whole, objective of the government. Censoring a few things to make an example of those things in order to put an atmosphere of fear in people so that they censor themselves. Then the government doesn’t have to physically censor each and everything. Basically, it just creates fear so that people then start censoring themselves. So when I put out my stuff, I feel scared, and I feel like, should I be posting this? When I did ‘River of Story,’ there was the publishing organization, and there were others in the organization, and it was like a collective responsibility, but when you’re posting by yourself on social media, on the one hand, you reach a lot of people very quickly, but then there’s nobody to warn you. As an artist, when you create something, it’s very hard to be objective and say if this crosses a line or am I stepping into a thing that’s going to get me into trouble? So it’s very difficult to know that. But usually, when I put out something which I feel is kind of borderline in terms of what it’s saying or doing, I do hesitate and think about it. But to date, I have never stopped myself from it. Even though I feel afraid, I still go ahead and post it.

Vox: Do you get trolled, or do you receive threats?

Orijit: Oh yes, lots of online trolling, online threats, phone calls. Even midnight calls! A couple of times, it even got quite scary. Interestingly, I was talking about this the other evening when I met a human rights lawyer because of one of these more serious kinds of threats. She looked into my work and suggested quite an interesting idea. She suggested that people are usually afraid to go after someone who is visible in the public space because then they are afraid of a certain amount of backlash. So ironically, probably the way to be safer is to create more such work because then you continue to remain in that public eye, and they will think twice about doing something. She gave the example of someone like Arundhati Roy. She said they’re scared to actually touch her because she’s too well-known a person, and if they arrest her, there will be a lot of protests from all quarters, not only within India, but that’s so she said if you’re in this position now, I would suggest you do more. It’s like riding a tiger, and you can’t once you’re on it, you can’t get off, you just have to go faster and faster on it.

I feel like I have gotten used to it by now, I think courage is not about not feeling fear, courage is about fighting that fear. And that is why self-censorship is something I keep talking about it. Don’t censor yourself. Don’t let that fear permeate into you.

Vox – Do you think psychedelics help artists in any way?

Orijit: I think that depends on the artist. I wouldn’t say it’s a necessity or every artist must do it, but I think it gives you a different perception about certain things, such as colors. It also depends on your personality and what you’re trying to do, what interests you. I was never one for using any of these substances simply for recreation.

I think what psychedelics do is that through artificial means, they put your brain into a kind of state which may be somewhat like that heightened consciousness that comes with maybe deep meditation or spiritual experience. But I have seen a lot of people who just end up getting lost in that whole thing because they are just doing it out of the sense of some kind of sensory experience, and maybe there’s a limit to that, right? I’m not somebody who propagates psychedelics, but if you know why you only use it and you are kind of doing it with a larger purpose, and you’re interested in it, then sure, why not?

Vox: Do you have a message that you want to give to the readers?

Orijit: It will sound very cliche, but sometimes cliches are cliche because they are true. You must have some kind of faith in yourself in whatever you do, and if you feel passionate about something, consider yourself lucky. Passion is what will take you places, it is what will drive your life, and it’ll take you through bad times.

It’s not always necessary to pursue it professionally. You could do a day job and still be passionate about music. I think that’s what is going to save you. Art saves those it seduces. If you are seduced by art or by anything, then it’ll save you at the end of the day, provided you go with it and you have faith in it.

Credits- Abhimanyu Sethia, Aditya VS, Gauravi Chandak, Mayur Agrawal, Nishanth S, Rahul Jha, Shreya Nair, Zehaan Naik

Edited by- Aarish Khan, Mutasim Khan, Sanika Gumaste

Thumbnail- Praneat Data