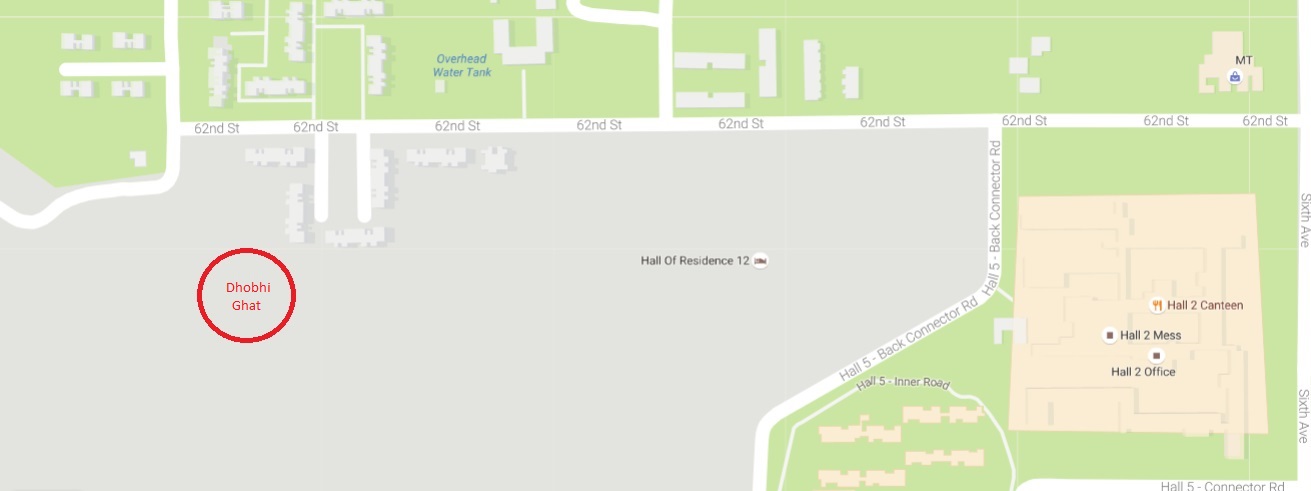

With a history almost as old as the institute itself, the Dhobi Ghat of the campus could be well seen as a place lost in time and circumstances.

As one enters the area, they are greeted by a narrow brick path strewn with cow dung that goes ahead meandering through colourful shacks, many of which are roofed only by tin sheets. Hundreds of bamboo cloth stands shoot up from the tall, unkempt grass in the encircling ground. Water streams through the dozen washing tubs. Standing under a kaleidoscope of colours created by light streaming in through the hundreds of cloths hanging around, watching kids carrying piles of jeans as they smile back at you, it is difficult to accept that one is still inside the campus of IITK.

However, Dhobi Ghat seems to be deep rooted with problems. The melancholic tales of everyday life as recounted by the Dhobis echo cries of negligence and indifference, and clearly depict the state of deep distress in which they have been living here all this while. Cows and bulls merrily amble by, wrecking cloth poles and people alike on their way. Pests abound the place, with snakes and scorpions inhabiting the grass the children play in. The Dhobis complain of the infrequent cutting of grass by Institute authorities. To verify their claim, we visited the IWD and confirmed from them that grass cutting in Dhobi Ghat is done once a year only. Garbage lies heaped in piles all around the place. The place stinks and living conditions look pitiful.

The Dhobi Ghat is a strange place. There are some families who live in Type-I quarters while others live near the ghats. Initially, the dhobis near the ghats, each had one room allotted to them. Gradually as their families grew, they built temporary rooms with thatch and mud, entering which we were appalled to see the battered interior condition. Some of those rooms have ceilings at only six feet height and they are poorly lit by kerosene oil lamps. Electricity for them is so near yet so far. We also stumbled upon a larger truth – these “houses” had no bathrooms attached to them. As it is difficult to build a sanitation system without proper outside help, these people decided on doing away with toilets in their houses, and have been defecating in the open all this while. The dangers of this much discouraged practice need no elaboration. And to mitigate these, they have designed their own system of warning methods, and go to the lengths of ensuring that at least one member accompanies children and family elders when it is dark. The thought of living here even for a day sent shivers down our spine. We are unable to provide basic amenities to residents in the very campus that aims at producing cutting edge research and entrepreneurial advancements.

How these people continue to live here is a big surprise, that too when they have the fear of getting evicted any time. To quote the Chief Executive Engineer at the IWD, “These people have illegally built temporary constructions in the area. They can be evicted any time, but the institute does not plan to do so as they have a strong support group in the numerous faculty members and students of the campus.”

Despite such a plethora of difficulties, their only major concern remains the installation of washing machines in the students’ hostels. This is seen as a capitalist decision, and the ability of washing machines to thoroughly wash clothes is thoroughly questioned. They go on further to describe the thoughtful techniques applied by them to the age old process of washing clothes. Whether it be the care taken in the segregation of different colours, or the careful craft of skilfull hands of an entire family in removing dirt from the intricacies of fabric, one cannot help but laud the efforts put in by the dhobis in ensuring that the campus community wakes up to a clean closet of crisp clothes. They take pride in the execution of their trade and labour throughout the day and remain one of the background tracks of the music of the campus.

By Shruti Joshi, Homanga Bhardawaj and Navya Gupta