Where does our campus get water from? Is the drinking water we get drinkable? What are the globally accepted standards of potable water? How should it taste?

To seek answers to these questions, our team took readings from water samples around the campus, questioned the respective authorities, and looked into the flipside of the obvious RO solution. Here’s what we found out:

Where does the campus get water from?

Groundwater is the primary source of water on campus! The campus is equipped with ten bore wells, each of which is about 400 feet deep. Water pumped from these borewells is directly supplied to the halls by the IWD (Institute Works Department). The job of purification and installation of coolers falls under the purview of the respective Hall Executive Committee (HEC).

The other potential source of water is the Kanpur Municipal Corporation, however, the municipal corporation has not been able to set up a stable water supply inside the campus yet, due to transportation issues. Another significant source of water for the campus is rainwater. A total of 20 buildings on campus are equipped with rainwater harvesting pits.

To measure the standards of water supplied on the campus, our team went around the campus with a TDS meter and took readings from various water sources. But first, let us understand what TDS is.

What is TDS?

TDS stands for Total Dissolved Solids – it is a measure of the concentration of the dissolved solids in mg/L (i.e. parts per million). These solids, ranging from minerals and metals to organic material and salts, account for the water’s quality, suitability for consumption, and perceived taste. Hence, we use TDS as a metric to determine if the water is fit for drinking, cooking, and other relevant purposes. However, our approach comes with two caveats.

Firstly, TDS is only one of the many metrics used to judge the suitability of water. We can have a water sample with near optimum TDS levels, yet being unfit for drinking. This is because TDS is only a measure of the concentration of the dissolved salts, and does not tell us anything about which salts are actually dissolved.

Secondly, taste is a subjective parameter and thereby, is somewhat unrelated to the TDS levels. However, it has been found that water with higher TDS levels seems to have a heavier “metallic” taste. On the contrary, lower TDS levels are linked with virtually no taste.

What are the Accepted TDS Limits?

Three benchmarks are majorly used to analyze water quality – the BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards), WHO (World Health Organization), and Bisleri. The limits of acceptance vary only slightly between these three standards. These are the Bisleri standards:

- TDS levels between 50-150 are considered excellent for drinking

- TDS level up to 300 is acceptable for drinking, but the lower, the better

- TDS above 1200 is considered unacceptable

- TDS levels below 50 are also unacceptable for drinking because it lacks essential minerals, however, it is not harmful

Our Findings

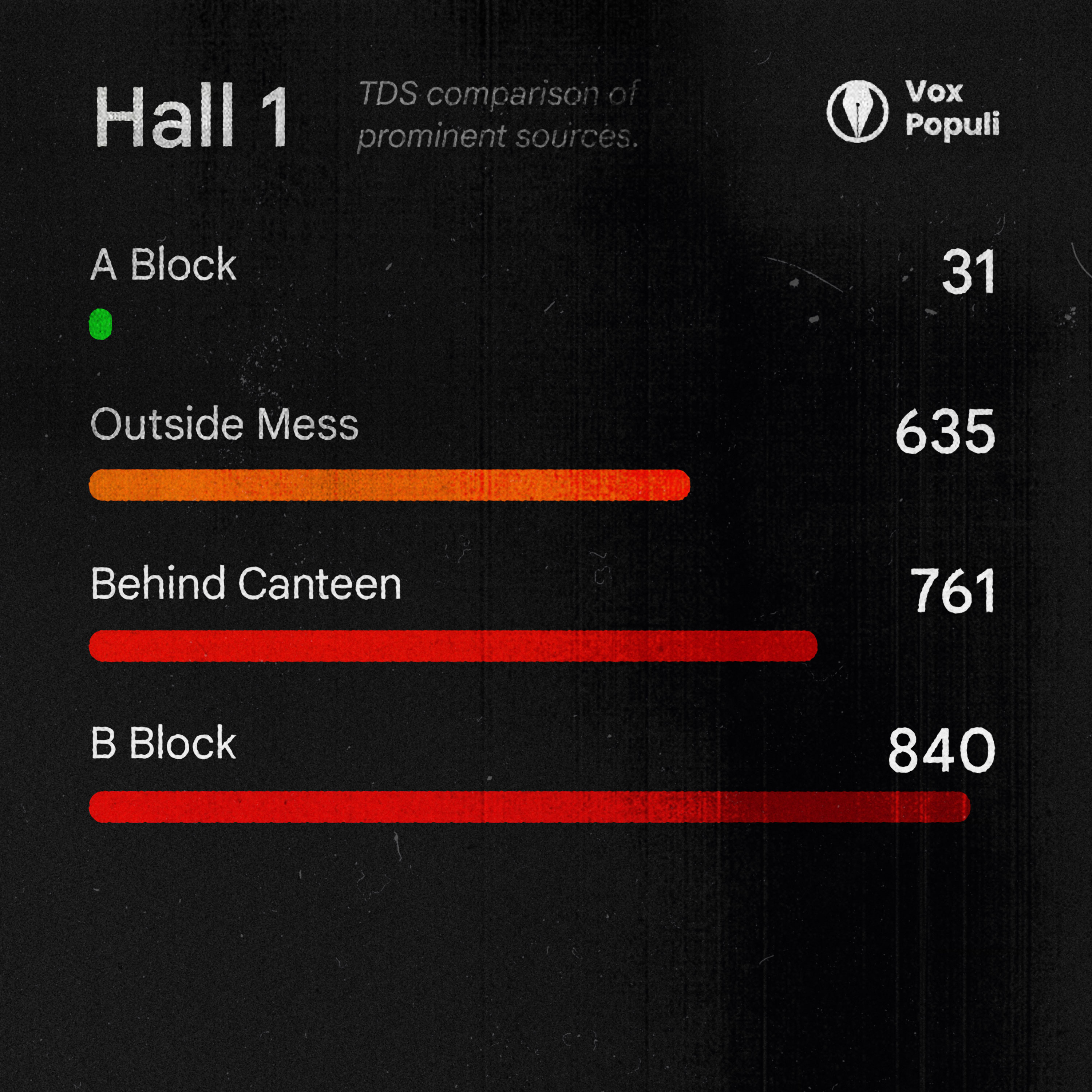

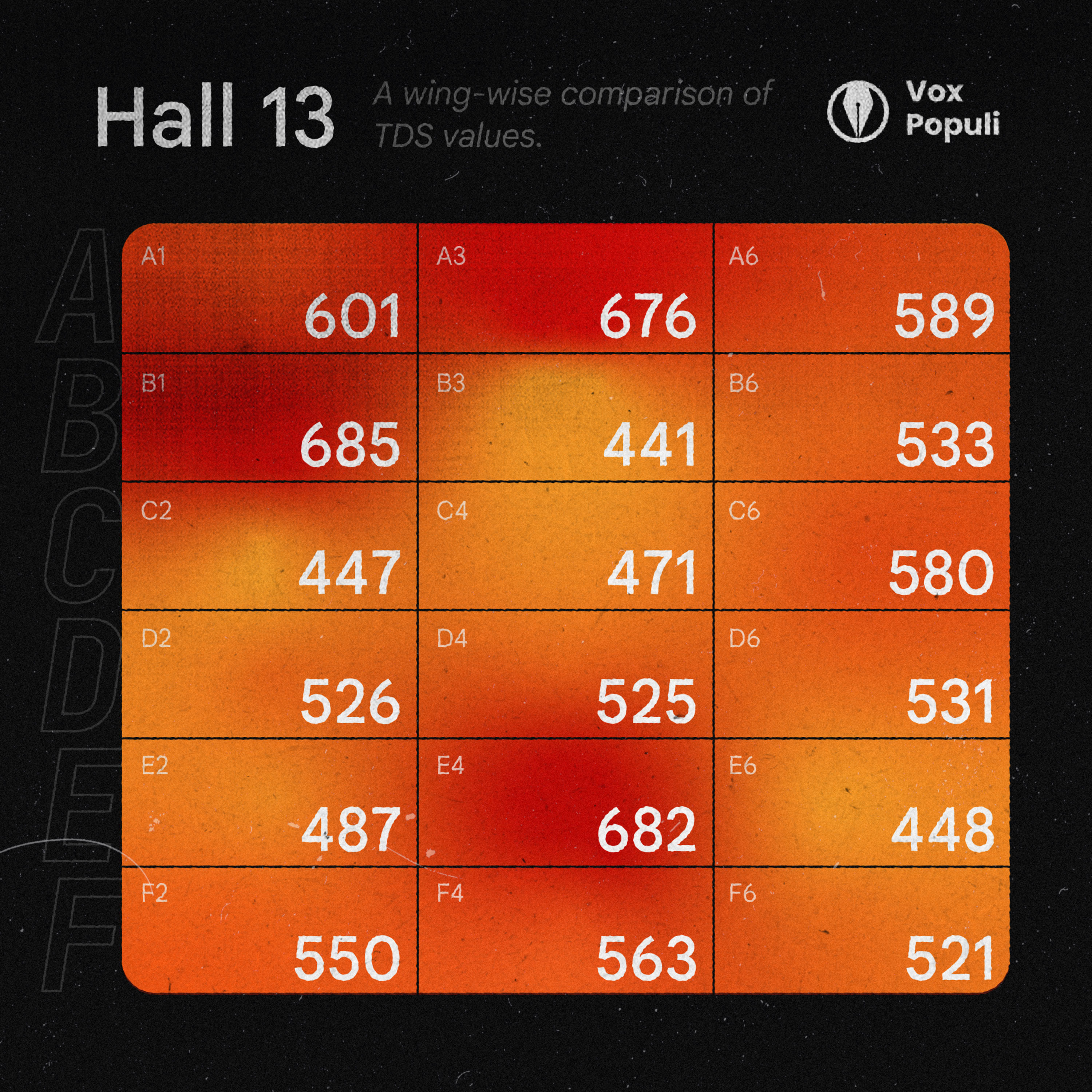

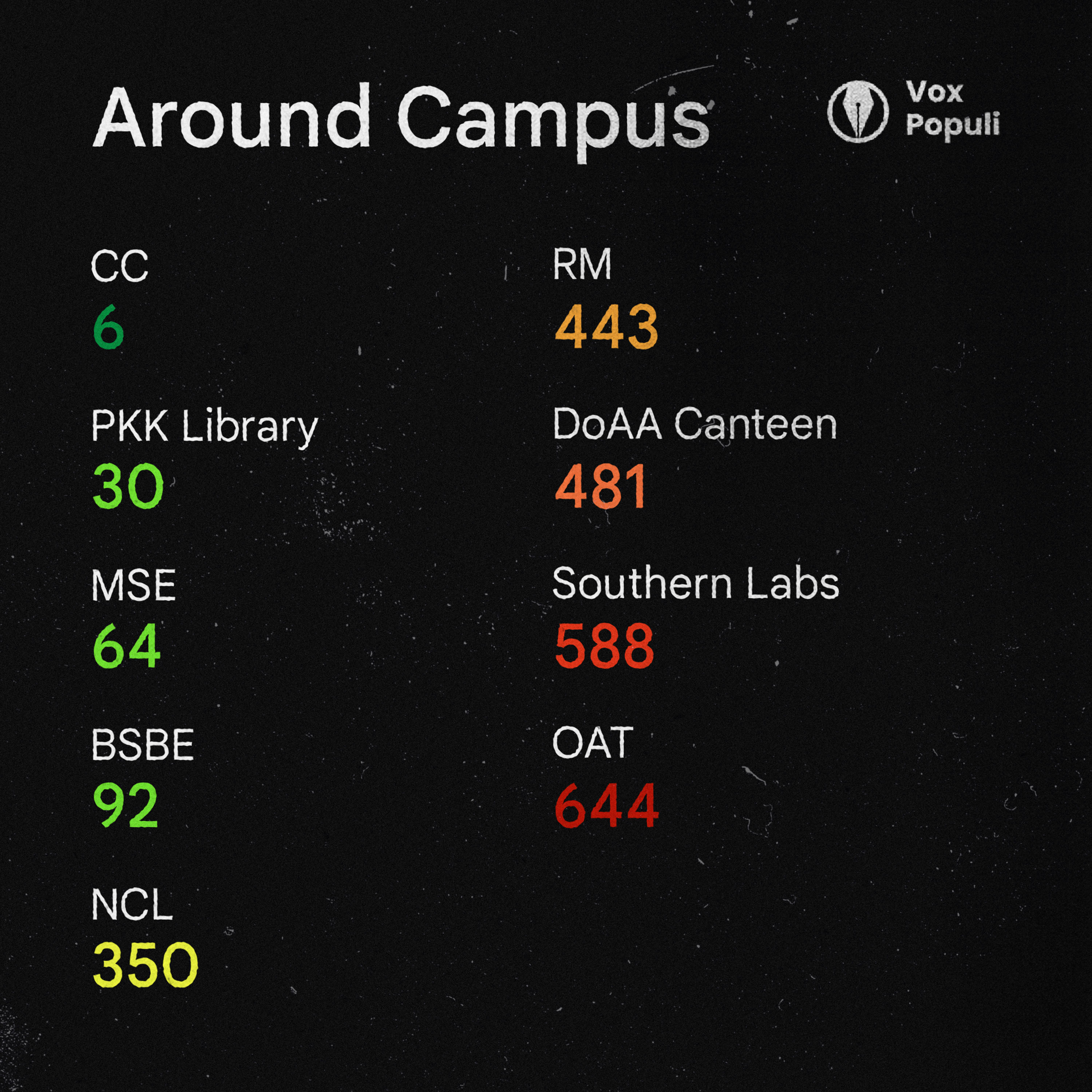

Our team took TDS readings from multiple water sources – both in residential halls and in public places like OAT and Academic Area. Multiple readings were taken from each source using this TDS meter, and the average of these readings has been used in the graphs below. Here are our findings:

As we can see from the data, the water quality in most halls of residences remains unacceptable. The water sources in the Academic Area perform better than the halls. This is also in line with the TDS level of water in Kanpur city, which is above 500.

Is RO the solution?

As per our study, RO seems to have improved the TDS readings of sources significantly.

Recently, Hall 6 installed a second 500-centralized RO (costing about 4.2 lakh, including installation charges and regular servicing of the machine), in addition to one RO already purchased in January 2021. This brought sharp improvement in TDS readings in the hall, as compared to the readings we took before RO installation.

Similarly, Hall 5, which is equipped with two centralized RO and another RO near the mess, displayed much lower TDS readings. This is in contrast with Hall 3, which has no centralized RO.

However, in 2019, the Supreme Court upheld the National Green Tribunal’s (NGT) ban on RO water purifiers in areas with TDS levels less than 500. The following reasons were provided for the RO ban:

Demineralization

RO often deprives drinking water of essential salts that are naturally present in natural water and provide us with essential minerals. In our study, this was most prominently seen in the water of computer center RO, which gave an astonishing reading of just 6ppm.

Water wastage

For every one liter of potable water, RO water filters push out three to four liters of water, as per broad estimates. According to the Water Quality India Association, RO achieves 20-30 percent purified water and 70-80 percent is drained which is not disposed of properly. Some manufacturers, however, claim that their brands result in minimal reject water and up to 60 percent purified water.

Hence, installing ROs to improve water quality needs to be looked at with a more nuanced lens. Improvement in water purity at the cost of questionable water quality and large water wastage needs to be studied in more detail.

What does the admin say?

In response to the data obtained, our team talked to a few officials in the IWD office. We came to know that the IWD receives regular, often strongly worded complaints from students regarding the installation of RO purifiers in halls, and of how an RO purifier is akin to a “basic necessity”. This indeed seems to be the mainstream perception of ROs.

The dysfunctionality of the Hall office, central stores, and DOSA offices during the covid pandemic stalled the completion of formalities for the purchase of ROs, leading to an extended period of dependence on mineral water and water from the mess, and few buildings in the academic area.

In the last few years, the water quality has improved significantly as more and more residential blocks are getting RO purifiers. But is the RO solution sustainable? And if not, what lies ahead?

Written by: Gauravi Chandak, Mohika Agarwal, Mutasim Khan, Rudransh Goel, Shreya Nair, Shreya Rajak, Tarun Goyal

Design by: Deekshansh Vardhan, Vijay Bharadwaj

Cover Photography by: Praneat Data

Edited by: Ayush Anand, Sanika Gumaste