The educational terrain in India, especially for poor children, is very harsh – almost barren. Even a good seed will wilt away in the absence of any soil to nurture it. We should endeavor to prepare a fistful of soil every day to help these seeds germinate. Therein lies hope and this will lend meaning to our lives.

![]() After graduating from IIT Kanpur in 1975, Arvind Gupta took up a job with Telco, Pune, now Tata Motors, as an engineer trainee. Two years later he realized that he was not born to make trucks. There were too many questions plaguing him. “Why do people who toil the hardest, do the most back breaking work get paid the least? Why was the education system so rotten? Why did the poor have no access to quality education?” He wanted to experience life, participate in the struggle of workers, and instead of seeing the scorching headlights of trucks he wanted to see a gleam in the eyes of children – the joy of learning something new!

After graduating from IIT Kanpur in 1975, Arvind Gupta took up a job with Telco, Pune, now Tata Motors, as an engineer trainee. Two years later he realized that he was not born to make trucks. There were too many questions plaguing him. “Why do people who toil the hardest, do the most back breaking work get paid the least? Why was the education system so rotten? Why did the poor have no access to quality education?” He wanted to experience life, participate in the struggle of workers, and instead of seeing the scorching headlights of trucks he wanted to see a gleam in the eyes of children – the joy of learning something new!

In 1980 when Arvind quit his job at Telco, his mother came to his defense stating, “Good, now that he has quit his job he will do something worthwhile”.

A prophetic statement from a woman who herself never went to school. But she ensured that her four children went to the best school and excelled. Arvind has not disappointed his mother. Every day he has worked with children – perhaps learnt more from them than he has taught. For the last 30-years, he has been demystifying and popularizing science among children with toys from trash thus preparing the fertile soil which will one day nurture young minds to germinate into eager, creative, exploring, questioning adults.

Inspiration

In 1972 a lecture at IITK by Dr. Anil Sadgopal recounting his experiences of teaching science to village children in Madhya Pradesh stirred him deeply. Dr. Sadgopal did a PhD from Caltech and worked as a microbiologist with the TIFR. He was barely thirty when he quit his job to start Kishore Bharati – one of the first NGO’s in the Hoshangabad District of Madhya Pradesh. He was disgusted by the horrendous way science was taught in village schools. The Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme (HSTP) attempted to make science interesting for village kids who had no access to expensive labs. Arvind looked at the possibilities of designing simple fun experiments using easily available local, low-cost materials like matchboxes, coins, broom sticks, newspapers, cycle tubes, old electric bulbs, rubber slippers etc. This excited Arvind enormously. In 1978, he took one year off from Telco and worked with the HSTP. There he designed many appropriate teaching aids. One was the Matchstick Mecanno which used cycle valve tube and ordinary matchsticks to make a series of 2 and 3-dimensional structures.

Another person that inspired him was Laurie Baker, a British-born Indian architect, renowned for his work on cost-effective energy-efficient houses. Arvind calls him,”my college day icon.” As a very compassionate architect, Laurie Baker touched the lives of the poor. He used local materials, local designs to build very affordable houses for the poorest fishermen. In 1978, Arvind spent four splendid months working with this great man and learnt that the solution to problems of the poor can be found by delving deeper into their reality – by understanding local materials, designs and skills. Arvind recalls, “Baker was an amazing man – all the time joking, laughing, drawing cartoons making fun of himself and the world around him, but simultaneously doing dead serious work.”

George Washington Carver – the black scientist’s life and work also deeply inspired him. Born a slave he struggled hard against racism and worked for the good of all humanity

Finally in 1980, Arvind left Telco to pursue his passion. He joined the Vidushak Karkhana – a commune run by a group of socially sensitized IITians (Dunu Roy, Sudhindra Seshadri and Sanjeev Ghotge) in the tribal district of Shahdol. There the inmates lived a Spartan life – cooked and worked collectively, ran a mechanical workshop, and dissected and discussed the whole world. Here the “personal became political” and he was able to explore some of his deepest queries.

From 1981-83, he worked with a trade union of miners in Chattisgarh. To him, terms like ‘contract workers’ and ‘exploitation’ were mere words, bereft of any deep meaning. He thought of experiencing the life of the marginalized to make sense and understand them better. The three years were tough but deeply enriching. Many times the only meal was rice with salt; and bed was the union office floor. He brought out the union’s newspaper “Mitan” – and sold it on the mine gates. He also helped the union run a garage for repairing trucks and taught in their schools. Through this he gained first-hand experience of the deep struggle in the lives of the poor. The mining township had 300 dump trucks ferrying ore from the mines to the railway yard. Children of the miners were very creative. They made improvised dump-trucks using just two matchboxes. They used a matchstick lever to lift the loading platform of their trucks. This was his first insight into the amazing world of children’s creativity. He documented this Matchbox Dump Truck in his first book – “Matchstick Models & other Science Experiments”.

Beginnings….

Arvind was born in 1953, one of four children whose parents had never been to school. His father – a poor businessman was perpetually in debt. He greatly benefited from his mother’s wisdom. She gave him enormous self-esteem and high self-worth. His mother understood the value of education and made sure that all her four children attended the best English Convent in Bareilly (UP) – St. Maria Goretti School. When debts mounted she sold her jewelry to pay for the children’s school expenses. Arvind still remembers his math teacher, Mrs. Frey. “She was the best. She nudged us gently to relate things to real life. She realized that I was good in math but poor in English. So, she chatted with me for hours in English. Because of her generosity I excelled in English and passed with distinctions.” As a child he didn’t have many bought out toys. In a sense this was a blessing – because now he had to improvise his own toys. When he was 6 years old a relative gifted him a Mecanno Set – which had steel strips with holes, screws and pulleys. He played with it for years and made many more things than were listed in the brochure.

Arvind did well in school and topped his district in the Intermediate Board Exams. After 12th he got into IIT with an AIR of 218. He was 28th in the North Zone. Which branch of engineering to choose? He had no clue. So he asked all the 27 boys ahead of him as they returned after counseling. All had opted for Electrical. So he landed up doing Electrical Engineering.

The Time & the Place: IITK and the 70’s

Coming from a poor family and small town, IITK opened up a new magical world for him. The swanky infrastructure, astounding facilities, enlightened faculty and elite peer group did sometimes instill a sense of awe. But there were great opportunities to be seized.

Together with his friend Akhilesh Agarwal he did a lot of tinkering – they made a compressed air engine, a Wankle Engine and repaired numerous aero-modeling engines. For full three years both of them ran the aero-modeling and auto-club at IITK.

As a child Arvind read little. IITK made up for it. The best thing at IITK was the library. It opened from 8 AM to midnight and one could issue 10 books. He used to read a lot – 6 newspapers every single day! He got addicted to the Economic & Political Weekly(EPW) and voraciously lapped up the Calcutta Diary by Ashok Mitra. This helped him see his own experiences in a perspective. All 5-years, he got the merit-cum-means scholarship. So, it was cheaper for his parents to keep him at IITK, than at home! This meant he spent a lot of time at IITK even in holidays.

The 1970’s were politically very volatile years. Students were out on the streets of Paris challenging authority. Anti-Vietnam, civil rights movements were rattling America. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring ushered in the environment movement. Intellectuals were swearing not to participate in war research. There was revolution in the air.

Arvind was drawn to political activism right in his first year. The Director had suspended Prof. A. P. Shukla – a distinguished physicist from Princeton for his left-leaning activism with the Karamchari Sangh. In protest the students decided to take out a march. He decided to join in. He was perhaps the youngest amongst the protesters. The rest were all MTech and PhD students. There were hardly any BTech’s. Students marched from one hostel to another. Some protestors carried placards and banners. As a young novice he was the only one shouting, “Comrades come out! Protest!” Some of the PG students got jittery at the word ‘comrade’ and asked him to shut up. He was too naive to understand the political ramifications of ‘comrade’. To him it simply meant a friend. The march ended by pissing in front of the Director’s House! This was Arvind’s first explicit political act!

A few intellectuals in IITK in 70’s were sympathetic to the Naxalite movement. They endlessly discussed the ideology of ‘class conflict’ and ‘seizure of state power’ over umpteen cups of coffee and Charminars.

Such empty talk didn’t attract him. They sounded vain. “Why don’t they do something about the plight of the mess servants?” Arvind would ask, “They serve us from early morning till late at night. Still their children don’t get admission in either the elite Campus School or the Central School.” Some of his class mates placed more faith in small positive action than in empty rhetoric. They were doers. So, he joined a group called SAHYOG – which helped teach the children of the mess servants.

They went from room-to-room collecting Rs 5/- per month pleading with hostel mates to “help a poor child go to school”. Some people were kind and paid. Others slammed the door on their faces and threw them out. He taught for a long time in the Opportunity School – a makeshift school for the underprivileged run in a Type II quarter.

In TA-204 Arvind and Akhilesh swore not to make a ‘silly’ project which would gather dust and ultimately mingle into rust. So they decided to do something ‘socially useful’ for the community. So, they made a ‘see-saw’ for the Opportunity School. They got the kids to do Shramdan. They dug two pits and finally grouted the ‘see-saw’ in place. Once a week he used to bunk classes to teach in the Opportunity School. They also held evening tutorials – helping children with difficult concepts or their homework. He spent the last 3-years in Hall V where he taught at least a dozen children from the Nankari village. They finally cleared their High School Exams.

Around 1970 Dr. Man Mohan Choudhary started the Le Montage – a film club. In five years the films club screened just about every film by Kurosawa, Bergman, Fellini, de Sica and Satyajit Ray. ‘Wages of Fear’ and ‘The Bicycle Thief’ was screened at least thrice. The student’s saw the world’s best cinema and listened to the country’s best musicians. All this had a profound effect on his sensibilities! There were extra-mural lectures by luminaries – Dr. Anil Sadgopal, Noble Laureate Gunnar Myrdal and Hindi writer Bhishma Sahni.

Arvind recalls, “A good institute does something to you without you knowing it. It slowly creeps and seeps under your skin – every pore of it. And that is what IITK did to me – it shaped my thinking, my character and prodded me to do something worthwhile than just make money.”

His first semester English teacher was the very enlightened Prof. Suzie Tharu and The Little Prince was his text book! The many social science courses – Philosophy, Political Science, and Economics challenged him to view issues from different angles – to look beyond the narrow ‘technical’ viewpoint. IITK certainly gave him a holistic perspective.

The defining political slogan of the seventies was:

“Go to the people, Live with them, love them,

Start from what they know. Build on what they have.”

Mission – to get the gleam back into a child’s eyes

Arvind has attempted to put the joy back into learning science. He has designed 1000 low-cost teaching aids and toys for learning science. These activities have been documented in clear sequential photographs with crisp instructions into books and videos. His team has also made 470 short films (1-2 minute duration) on how to make these learning aids. These films dubbed in 18 languages show the whole process of making and playing with the toy. Currently he has 3400 short films on YouTube with over 40,000 viewers every day. In the last four years these films have been viewed over 15-million times. Friends and volunteers help in dubbing these films in many world languages. When children see a film in their local language it makes a lot more sense to them. All this educational material can be downloaded freely from his websitehttp://arvindguptatoys.com/

![]() Over the years he has translated hundreds of books on education, peace, science, mathematics and great children’s literature into Hindi. He has also presented over 145 films for the NCERT science programme titled Tarang. These films have been repeatedly beamed on Doordarshan. He has conducted workshops in over 2,500 schools across the country – many of them with municipal and poor schools. This is how he describes his experience after each workshop, “After every workshop I see smiles on the faces of the children. There is gleam in their eyes. These have been my most fulfilling moments. I see hope.”

Over the years he has translated hundreds of books on education, peace, science, mathematics and great children’s literature into Hindi. He has also presented over 145 films for the NCERT science programme titled Tarang. These films have been repeatedly beamed on Doordarshan. He has conducted workshops in over 2,500 schools across the country – many of them with municipal and poor schools. This is how he describes his experience after each workshop, “After every workshop I see smiles on the faces of the children. There is gleam in their eyes. These have been my most fulfilling moments. I see hope.”

To reach far flung remote Indian villages with little internet connectivity a DVD titled The![]() Learner’s Library has been collated. It contains 1000 amazing E-Books on Education, Peace, Environment, Science, Mathematics and great Children’s Books plus 220 short videos on Toys-from-Trash plus 6000 photographs with instructions to make simple science models. All this is packed in a single DVD! This DVD (currently in Marathi, Hindi and English) has been shared with over 7000 schools for free. Apart from this, every week Arvind’s team holds two free science workshops for school children. In each workshop 50 children from a municipal school participate. They spend 4-hours seeing some amazing science demonstrations and also make 10 simple science models with their own hands. The children take back what they make.

Learner’s Library has been collated. It contains 1000 amazing E-Books on Education, Peace, Environment, Science, Mathematics and great Children’s Books plus 220 short videos on Toys-from-Trash plus 6000 photographs with instructions to make simple science models. All this is packed in a single DVD! This DVD (currently in Marathi, Hindi and English) has been shared with over 7000 schools for free. Apart from this, every week Arvind’s team holds two free science workshops for school children. In each workshop 50 children from a municipal school participate. They spend 4-hours seeing some amazing science demonstrations and also make 10 simple science models with their own hands. The children take back what they make.

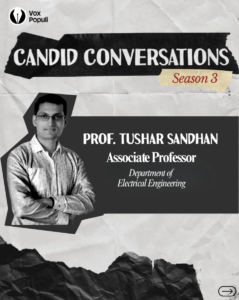

In 2003, Prof. Jayant Narlikar (Padma Vibhushan) India’s most celebrated Astrophysicist invited Arvind to work at the Children’s Science Center of IUCAA (Inter-University Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics) located in Pune. Here, a small team of four – very ![]() passionate and wonderful people work out of a 400-sq ft room. Surrounded by junk, the 59-year-old Arvind, in his corduroys and khadi kurta, walks around barefoot, creating teaching aids which he lovingly call “toys”. Gupta’s office/lab is littered with finds from the local bazaar, garbage cans, old bottles etc. There are broken CDs, used Tetrapaks, bicycle valves and tubes, film rolls, magnets, plastic straws, used refills of ballpoint pens, all types of paper, worn-out bathroom slippers, matchsticks and matchboxes, mirrors, bangles and combs. Hanging from soft-boards, wall nails, doorknobs and handles are Tetrapak butterflies, needle and thread acrobats, paper birds, spiders and skeletons.

passionate and wonderful people work out of a 400-sq ft room. Surrounded by junk, the 59-year-old Arvind, in his corduroys and khadi kurta, walks around barefoot, creating teaching aids which he lovingly call “toys”. Gupta’s office/lab is littered with finds from the local bazaar, garbage cans, old bottles etc. There are broken CDs, used Tetrapaks, bicycle valves and tubes, film rolls, magnets, plastic straws, used refills of ballpoint pens, all types of paper, worn-out bathroom slippers, matchsticks and matchboxes, mirrors, bangles and combs. Hanging from soft-boards, wall nails, doorknobs and handles are Tetrapak butterflies, needle and thread acrobats, paper birds, spiders and skeletons.

Everyday 10,000 passionate books are downloaded from his website. All for free. His reward: a sense of deep gratitude to be able to do something meaningful for the poorest children of the world. The Science Center’s mission statement is – “Get the gleam back into a child’s eyes.”

He believes in Copyleft NOT Copyright

There are 400-million Hindi-speaking people who have little access to good reading material. There is a tremendous paucity of good books in Hindi. With over a billion people there are no decent public libraries in India. One of his passions has been to translate good books for children in Hindi. Every day he spends three hours translating books into Hindi so that they can reach out to a larger section of children.

In 1998, the Pokhran blast shook his conscience. The response to these nuclear tests was uniformly eulogistic. Politicians across the board lauded this feat. Indian scientists vied for photographs dressed in military fatigues. This was deeply depressing for Arvind. He looked around and there seemed to be no books on peace in India – the land of Buddha and Gandhi. It was then that he came across a Japanese story called ‘Sadako and the Thousand Cranes’ – a true story about a girl named Sadako Sasaki, who was diagnosed with leukemia after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Sadako knew about the Japanese legend that folding a 1000 paper cranes would grant her wish. She did fold a few hundred cranes but ultimately succumbed to the atom bomb disease. Sadako died at twelve for no fault of hers. This story brought tears to Arvind’s eyes. He knew he had to translate it. There are now a dozen anti-war books, amongst hundreds of other translated titles on his website. “Our focus is to make valuable world literature available to our children in Hindi,” says Gupta.

Lokmanya Tilak said, ”Swaraj is my birthright, and I will have it.” Arvind has similar views on the sharing of knowledge. He says, “Knowledge is my birthright, and I will share it. Copyrights laws were enacted in the caveman’s era – they make little sense in today’s digital world. The digital dream should be to bring every book, in every language available to every child on earth for free. And this is very doable.” He has digitizing thousands of out of print books on education and for children. He has been translating books that help children see new possibilities and expand their horizons. He claims, “The need to share knowledge is enormous. The response of civil society should be toshare. Not for money, but for the love of sharing. Whatever I do is a small effort towards doing just that.”

Science is not about burettes or pipettes

Having visited more than 2,500 schools, Gupta observed that in most schools the lab apparatus lay locked in cupboards and gathered dust. It is a myth that science can only be done in fancy labs with gleaming glass burettes and pipettes. Science has been made out to be a bookish affair in which you simply mug up definitions and formulae and spit them out in exams. But this is patently untrue.

For children, the whole world is a laboratory – they are always making things. Children are often traumatized by expensive equipment alienated from their own daily life. His slogan is, “The best thing a child can do with a toy is to break it.”

Why do children break toys? Because they are curious and want to know what’s inside it. This is what propels them. A well designed toy must welcome children to pull it apart, see its innards and put it back again. There is enormous possibility and potential in our children, if they are given a chance to discover things for themselves. “When children make things themselves, they gain a deep insight. They learn so much without being taught. For instance, the newspaper has a grain in one specific direction. Long strips can only be torn along the grain, not across it,”

The British Telcom ad sums the deadness of schools succinctly. “Children walk to school, children run away from school.” If we can link science to real life and real objects than it becomes magical. On Arvind’s website, one can find, for instance, a delightful centrifugal pump made from a drinking straw, a piece of a bicycle spoke and some sticky tape. Another is a totally unbelievable way of balancing ten nails on the head of a single vertical nail, which can be rocked. The nice thing about these toys is that they are made from absolutely low cost, locally available materials, with a strong recycling element.

We must not forget that most sacred and expensive thing in any “lab” is the child’s mind! Toys capture children’s imagination, teach them scientific principles, and encourage their curiosity. Toys from trash imbue another cardinal value TO DO MORE WITH LESS.

We need engineers to help those living on the ground

To encourage IITians to take up social causes, he suggests that first and second year students should spend a couple of days living in a city-slum or with a remote village community. This will directly expose them to conditions of depravity and dehumanization. Compassion and consciousness for the poor can come only through direct personal experience and not through lectures on poverty. These real experiences will make youngsters think, analyze and they will soon discover for themselves the real reasons for world poverty. Some of them will later on certainly take up more meaningful vocations then working for the war industry or destructive corporations. Arvind’s inspiration is a Young Oxfam Poster of the seventies:

“And somewhere there are engineers

Helping others fly faster than sound.

But, where are the engineers

Helping those who must live on the ground?”

=============================================================

Arvind Gupta has been conferred numerous awards for his work, including the inaugural National Award for Science Popularization amongst children (1988), Distinguished Alumnus Award by IIT / Kanpur (2001), Indira Gandhi Award for Science Popularization (2008) and the Third World Academy of Science Award (2010) for making science interesting for children.

Please feel free to contact Arvind Gupta (BT/1975) at arvindguptatoys@gmail.com

His website http://www.arvindguptatoys.com has FREE downloadable resources on education, environment, science, and toy making.