“Student representation is important for the overall development of students, so university statutes should make it clear that students can be represented.” -Lyndogh commission.

However, various questions have been raised on the EC’s efficacy in conducting ‘free-and-fair’ elections. Broadly, these questions may be divided into three themes: one, on the restrictive and ambiguous nature of the Code of Conduct; two, on ethical and legal problems with proofs and interrogation processes; three, on structural issues in the constitution of Election-related bodies (EC, GRC, AGRC). Vox team dives deeper into each of these and presents findings from our conversations with former election candidates and EC members. The article intends to critique elections in IITK as a structure and not the specific people involved in the Election Commission and its processes.

On the Code of Conduct & its Enforcement

The Code of Conduct (COC) issued by the EC defines a set of rules on what is allowed and not allowed during elections at IITK. However, there are various issues with how the Code of Conduct applies currently:

Firstly, multiple candidates complained that the penalties are decided on a case-to-case subjective basis as there are no clear guidelines on what violation attracts what penalty. It is easy to find multiple candidates violating the same clause of the CoC but being subjected to different levels of fine, ranging from mere warning to cancellation of nomination. One of the solutions proposed was the appointment of a bench of 3 CEOs instead of one.

Ex-Chief Election Officer, Prince Joel was of the view that not only the offence, but also the impact of the offence determines the fine imposed. Hence, he believed that compiling an exhaustive list of breaches is impossible as there will always be ways to get around it. As a result, the rules are written so as to allow the list to be enlarged as necessary. The present Chief Election Officer (CEO) also confirmed that the COC is flexible and dynamic and the rules are relaxed or imposed on a case-to-case basis.

Secondly, an issue that resonated with a number of candidates was that there should be a specified duration for which a fine from the COC can be imposed on them; they found it unjust to be punished for something they did long before the elections. “You can’t expect a person to know the code of conduct at that point, ie, 6 months or 2 months before.” One of the former candidates believes that if any major rules were broken before the election, the Gymkhana or Institute rules – and not the EC- should be in charge.

Samiksha Jaiswal, the present Chief Election Officer (CEO), rebutted the allegations by claiming that anyone who broke the rules before the Code of Conduct was put into effect were told about it right away. Even though the action is carried out later, a warning is given right away.

Thirdly, the COC says that any form of anti-campaigning is penalizable. Various students have found this restrictive as they feel one should be free to discuss shortcomings and negatives of other candidates, to make a responsible choice. When we asked the EC, they clarified that the candidate can be criticized based on their manifesto, and their present or past PORs, but personal remarks or soliciting votes against a candidate would count as anti-campaigning and attract a penalty.

Fourthly, former candidates found the monetary nature of the fines concerning as it puts people from well-to-do backgrounds at an apparent advantage. On this the CEO said, “This issue is being reviewed in the Senate. We haven’t been able to implement community service as an alternative to monetary punishments yet. Of the possible options, Prayas gave a negative review and NSS cannot be used as punishment.”

On Collecting Proofs and Investigating Offences

Firstly, the proofs that the EC collects consist of mostly audio/video recordings or chat screenshots of candidates/GBMs- taken and used without their consent (and in most cases, even without their knowledge). This method of collecting proofs raises serious concerns on breach of privacy as the EC has virtually assumed consent to record any conversations of any member of the student community for purposes of catching violations.

When we quizzed the EC officials on the issue, they rebutted by saying that access to the sensitive information is restricted to the Chief Election Officer and the person who recorded it – with the entire database stored on a cloud platform – such that only the CEO has access to it.

Secondly, the proof is never shown to the candidate being penalized, to protect the identity of the proof-provider. The proofs, if need be, are submitted only to the Grievance Redressal Committee(GRC) and the Appellate Grievance Redressal Committee(AGRC) for scrutiny. The only details revealed to the candidate/GBM are clauses of the Code of Conduct violated by them. A former candidate said that he was unable to defend the allegations against him in the GRC as he did not know the proof on whose basis his nomination was canceled. But he was rendered helpless due to EC’s policy.

A former candidate also pointed out that since the proof is accessible to only a few – if they anyhow try to tamper or manipulate the contents of it, there’s absolutely no check in place to prevent this from happening.

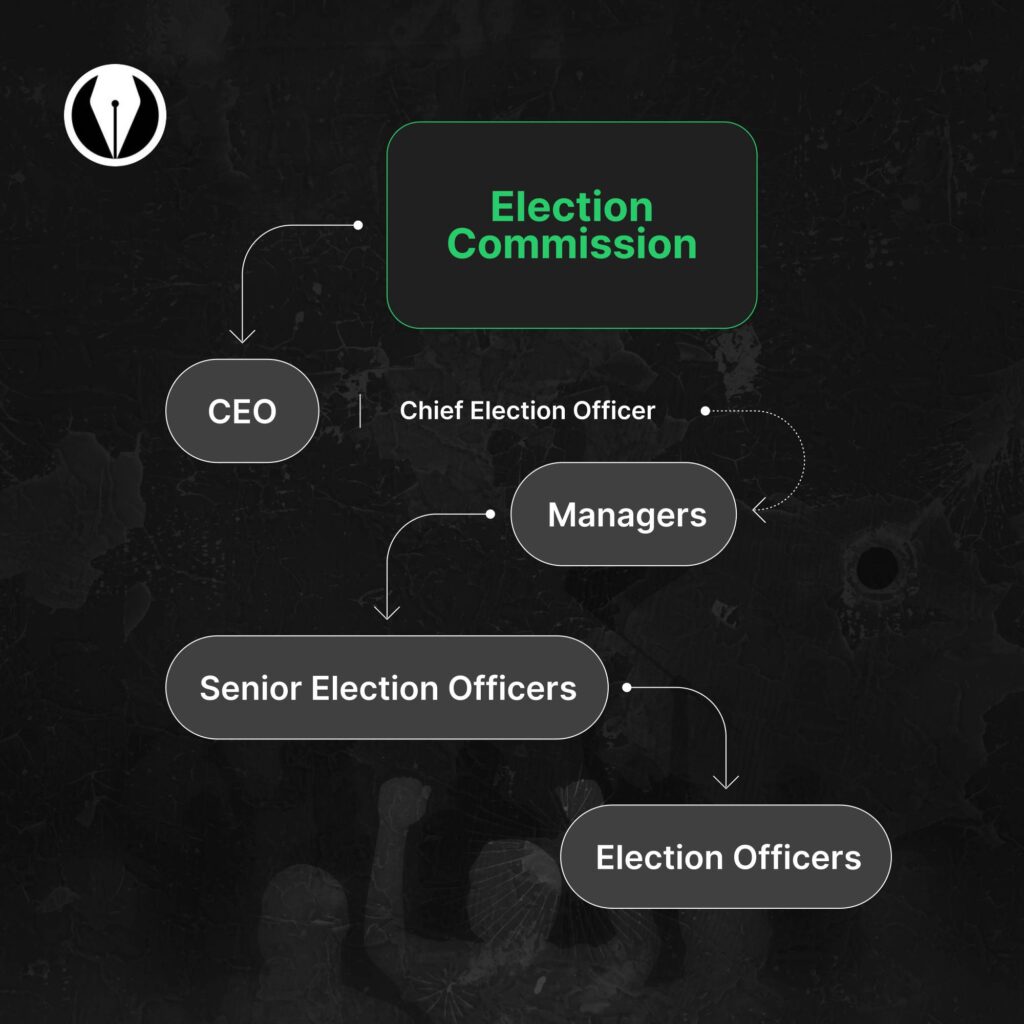

On Structural Issues with Election-related Bodies

In case a candidate wants to contest the decision of the EC, they may file a complaint with the Grievance Redressal Committee (GRC). The GRC – consisting of two professors and three student members – is supposed to act as a failsafe mechanism for any mistakes or biases of the EC. Once the GRC re-investigates the issue and gives its decision, if the candidate is still unsatisfied, they can approach the Appellate Grievance Redressal Committee (AGRC) for another investigation. Such an elaborate mechanism exists to infuse necessary checks and balances for any manipulation of the EC. However, despite that, the general consensus among former candidates was that they never got a fair opportunity to defend themselves in the redressal committees.

The indirect involvement and unreasonable influence of the Chairperson, Students’ Senate and the President, Student Gymkhana in the elections has been a common grievance for many previous candidates.

Firstly, the Chief Election Officer (CEO) is selected by a panel composed of the outgoing CEO, President and the Chairperson. Secondly, the 3 student members nominated to the GRC are selected by the nomination committee of the Senate. The President is the convenor of the committee and the Chairperson is an ex-officio member. Thirdly, as observed in the past, typically the Chairperson and the ex-CEO are nominated to the GRC.

Hence, such a structure steers clear of any division of power and instead allows the current position holders to pull all the strings. Moreover, former candidates we talked to don’t trust the GRC as a failsafe mechanism against any biases of the EC – as the same position holders who are pulling the strings at the EC, are members of the GRC.

An ex-candidate whose nomination was canceled remarked that as the then Chairperson wasn’t very fond of him, he, along with the ex-CEO (GRC member) and then CEO, fabricated proofs against him. As the Chairperson was also a part of the GRC, he claims that there was no way to stop this abuse of power. Although it must be noted that the names of the student members of the GRC are presented in the pre-conduction report of the Elections in the Senate and any contentions can be raised on the floor of the Senate.

Another candidate suggested that the CEO should be chosen via discussion and voting in the Senate, just like the CoSHA Convener or Chairperson are elected in the Senate. This method could make the process more transparent and induce a sense of faith in the neutrality of the EC.

An ex-CEO, who was also a GRC member, pointed out,“the issue is that the Senate doesn’t make the GRC properly. When you see the Chairperson or the ex-CEO in the GRC, even if they may not be biased in the meetings, but they are perceived to be biased in the eyes of the people. The Senate should choose people who are connected to the Senate and active in the student body, but not directly related to the EC or any candidates.”

Conclusion

Hence, the elections and its associated processes and structures are riddled with a number of nuanced problems. As a student community, we must indulge in answering these complex questions: how should the Code of Conduct set a balance between allowing healthy debates and discussions while avoiding any nuisance? What safeguards may be put in place to make sure the EC does not breach the privacy of students? How can the structure of selections and nominations in Election-related bodies be evolved to ensure appropriate checks and balances and shield the EC from undue influence of any one set of people?

1The Lyngdoh Committee report may be read here- https://www.ugc.ac.in/oldpdf/students_pdf/lyngdoh_committeemhrd2712.pdf

Written by: Aman Arya, Gauravi Chandak, Mehar Goenka, Rudransh Goel, Zainab Fatima

Edited by: Abhimanyu Sethia, Sanika Gumaste

Design Credits: Praneat Data, Sachidanand Navik