Attendance has long been a moot point of discussion amongst both Professors and Students. As the semester begins, a few FCHs manage to send shivers down one’s spine with their attendance policies. In an attempt to understand the views of Campus Junta, we at Vox Populi conducted a survey on the “Effect of Attending Classes and Attendance Policies” and simultaneously met a few professors to gather their opinions on this topic.

What follows is a list of questions we compiled on the effect of Attendance policies, answered by various professors, along with the data we collected from our survey.

From our survey of 457 respondents, 260 people claimed that they attend all or most of their classes; 108 people opined that they attend classes around quizzes and important topics; and 85 people said that they rarely attend classes.

When we asked the professors about the attendance they usually see in class and whether it bothers them, Prof. P.S. Ghoshdastidar stated that he usually sees low attendance after mid-semester exams since “students become very complacent because they are assured of a decent grade after looking at their mid-semester performance.”

Prof. Manindra says that attendance does bother him. He recalled teaching a class of 350 students in the previous semester and noted that he never saw more than 100 students attend the class. He attributes the fall in attendance to the post-pandemic scenario, where students have more access to online resources, which might have affected their motivation to attend physical classes.

This sentiment is echoed in our survey as well, where 76 percent of respondents said they wouldn’t attend the class offline if the same lecture were available online.

Among other factors deterring students from attending classes, early morning classes (opted by 314/421 people), very few classes or long intervals between classes on the same day (opted by 165 respondents) seemed to be the prominent factors.

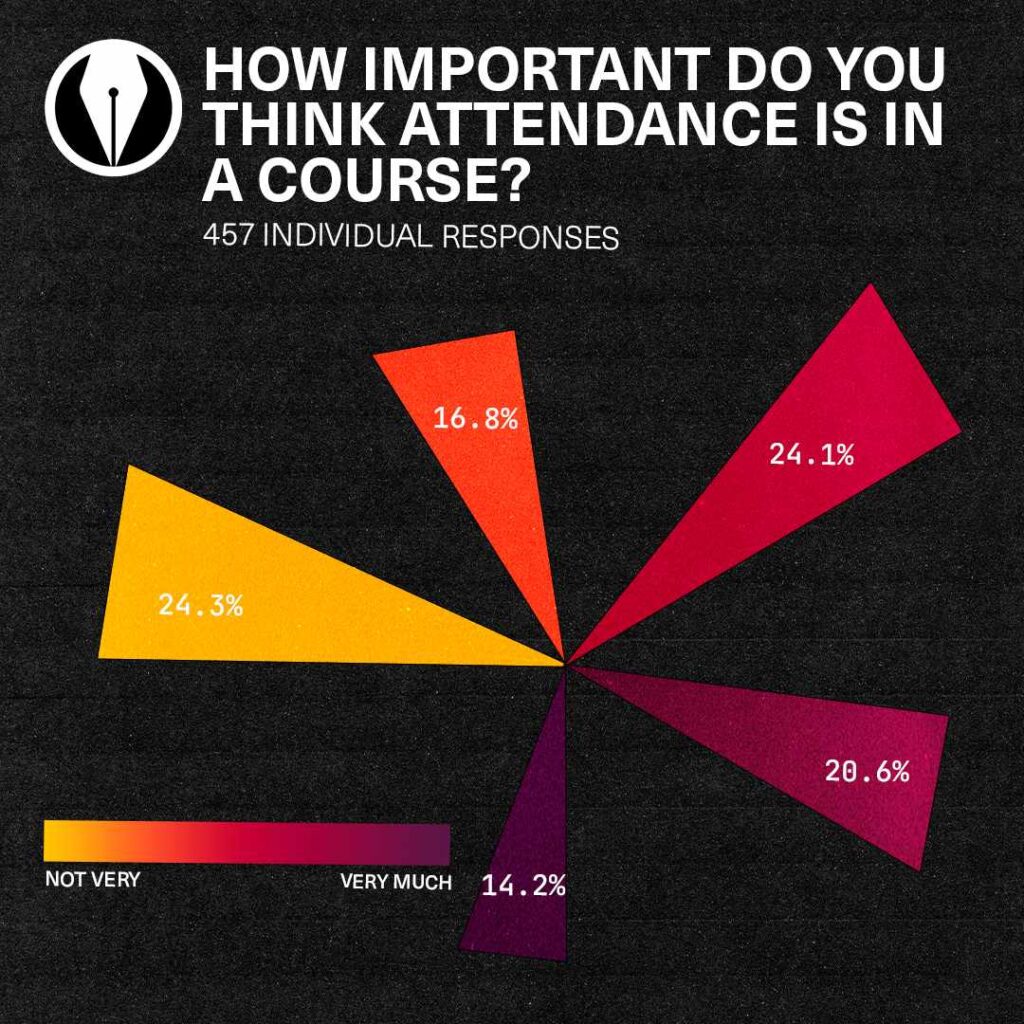

When we asked students to rate the importance of attendance on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being not at all important and 5 being most important, out of 457 respondents, the majority gave it a rating of 3 (110 people) or 1 (111 people). Only 35% of respondents gave a score of 4 or above.

On the other hand, all professors agree with the strong correlation between attending classes and students’ performance in courses. Prof. Ghoshdastidar states “The courses at IITK are uniquely structured, and the way content is presented is very different from any other platform. Therefore, even if a student misses a single class, they are definitely going to face some difficulty understanding the course, which is bound to affect their performance.” He also presents a correlation he could gather from his courses: “Most students who don’t attend classes regularly don’t even score enough to get a C; they mostly land with a D or an F.”

Prof. Harbola further adds, “In my courses, at least, I make sure that it is essential for students to attend classes to perform well, and I structure them very differently from any other course available online. My motivation as a teacher is to ensure that tomorrow when a student meets a person from MIT, they look them in the eye and say, I learned better than you did.” He further elaborates on the importance of attendance and teacher-student interaction and makes it clear that attendance is bound to impact performance.

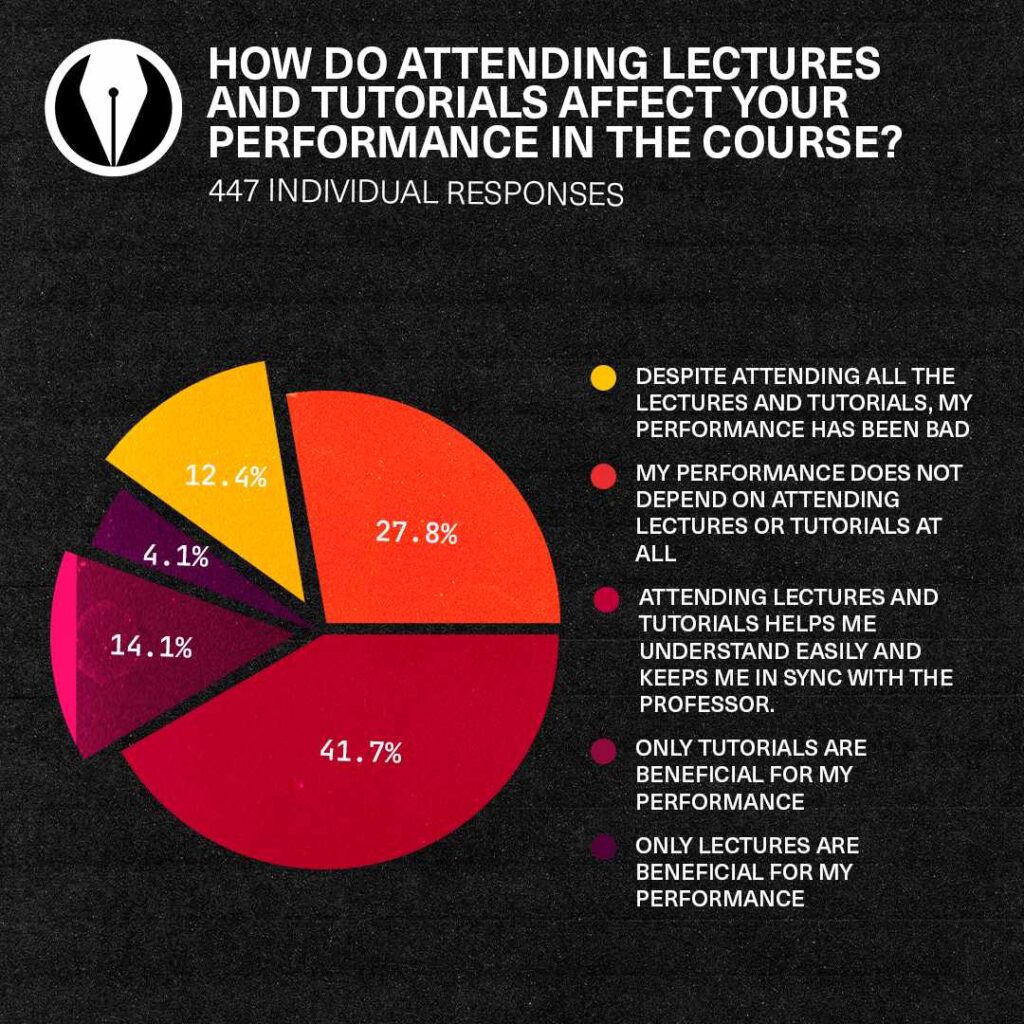

When we questioned students on the correlation between attendance and performance, out of 447 respondents, 42% believed that attending lectures and tutorials helped them understand easily and kept them in sync with the professor. In contrast, 28% felt their performance was independent of attending lectures and tutorials.

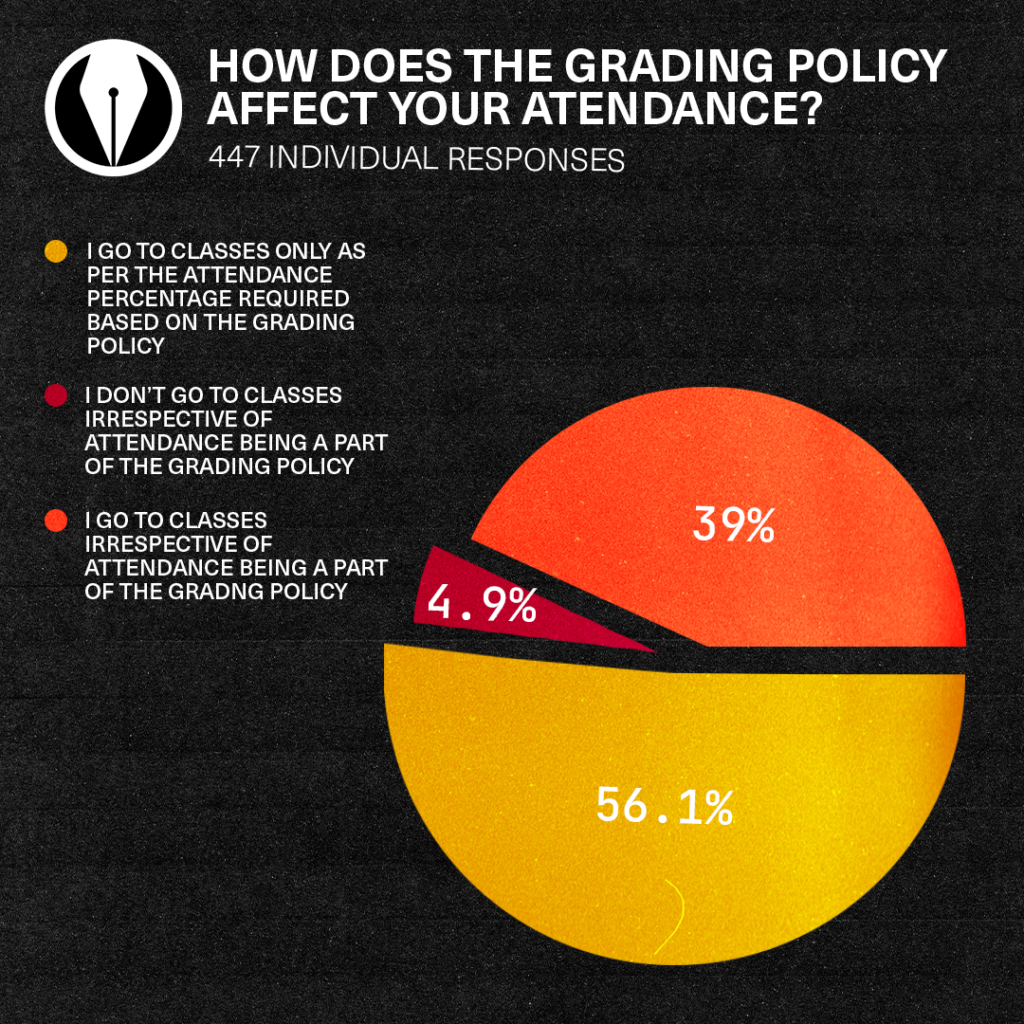

Upon closer examination, our survey pointed out that another major factor that decides whether or not one attends their classes largely depends on the attendance policy of that course, as 56% of students said that they go to classes only as per the attendance percentage required based on the grading policy.

Professors hold great power in deciding what this policy would be, as unlike most colleges, there is no institute-wide attendance policy, and professors are free to determine how to incorporate attendance into their courses if they choose to implement it at all.

Professor Arijit Kundu, who mandates 90% attendance in his course, says, “The Motto behind 90% attendance is just to push the students to wake up and come to class,” implying that the main reason behind enforcing a set percentage of attendance is to ensure consistency, especially considering the ample extracurricular activities here on campus.

In the same context, in one of our previous articles, Prof. Neeraj Misra states that “Some students may be capable of achieving good grades without regular attendance, but IITK is not a factory to provide grades. Here we inculcate an academic environment, and every student has certain responsibilities.” He further elaborates that attending classes is the fundamental academic responsibility of a student and is bound to impact their learning.

Moreover, in certain courses, instructors assign a portion of the grades to attendance, leading to the question of how significant this practice is in influencing a student’s learning and overall academic performance. Professor Tapobrata Sarkar believes that “enforcing” attendance might not necessarily have a significant impact on a student’s learning or overall grades. Instead, he focuses on creating an enjoyable and engaging learning experience. He aims to impart knowledge that students can apply in their later lives. Similarly, Prof. Harbola shares the same view as Prof. Tapobatra .However, he conducts surprise quizzes in the tutorials.

“We say continuous evaluation. I’ve changed it to continuous study. What is wrong with that?” ~ Professor Harbola

Nonetheless, professors have time and again tested and experimented with attendance policies. While some have stuck to the same policy from the very beginning of their careers, others have changed with the tide.

Professor P.S. Ghoshdastidar mentions how, in the beginning, he didn’t enforce any attendance policy in his classes; however, now he has a certain weighting of attendance in the grading. He remarks, “I joined in July 1984, and until 2000, there were no complaints from any faculty member regarding students not attending classes. The attendance began to fall in the Y2K batches. I think this is due to easy access to the internet, and the students get the material online and don’t attend classes.”

Prof. MK Harbola says he used to have an attendance policy for smaller classes but not for larger classes; however, later, he realized that his role was to teach and not enforce attendance on students. ”People are here to study; they don’t want to study. Why should I force them? That’s their problem. They are wasting their parent’s money.”

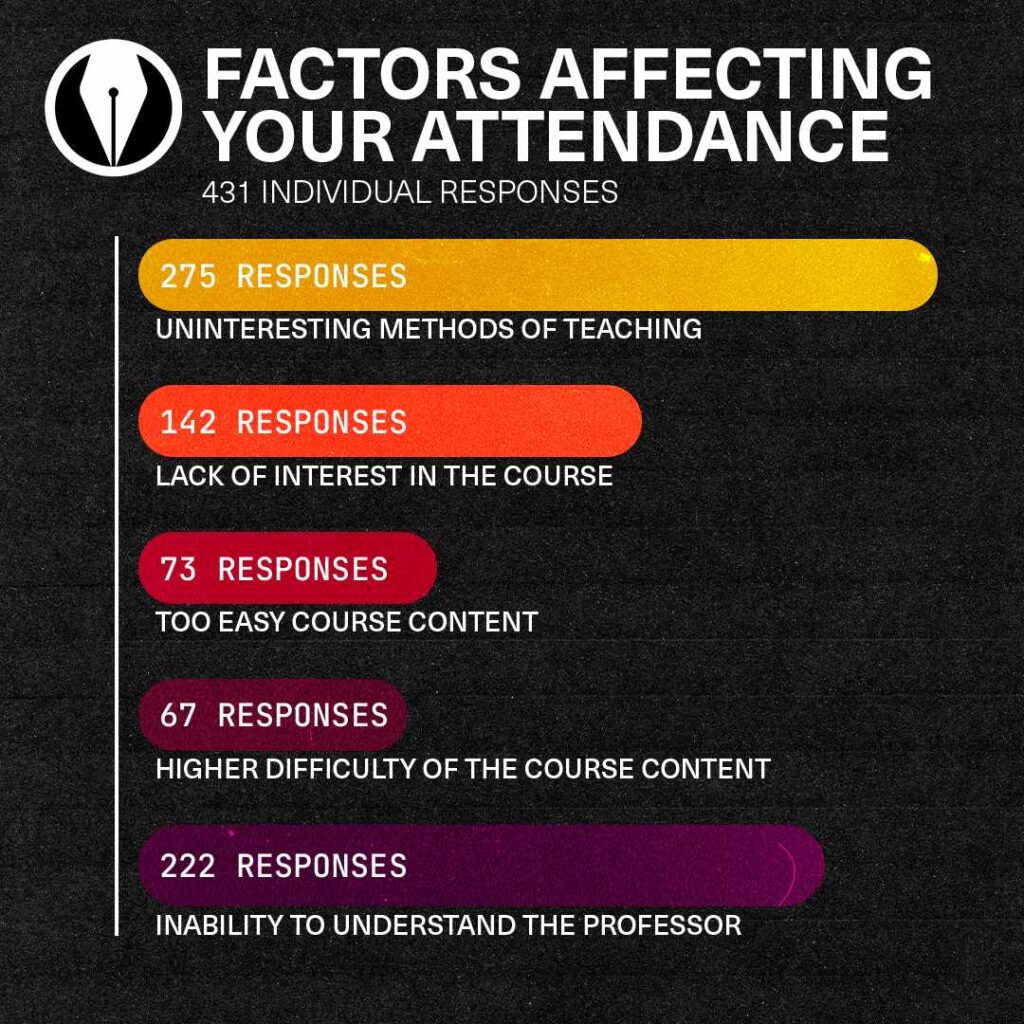

Despite graded attendance and changes in the instructor’s policy, we see that there are some pertinent issues due to which students do not attend classes. According to our survey, the three leading causes are uninteresting teaching methods (275 respondents chose this ), difficulty in understanding the professor (222 respondents), and lack of interest in the course’s subject (142 respondents).

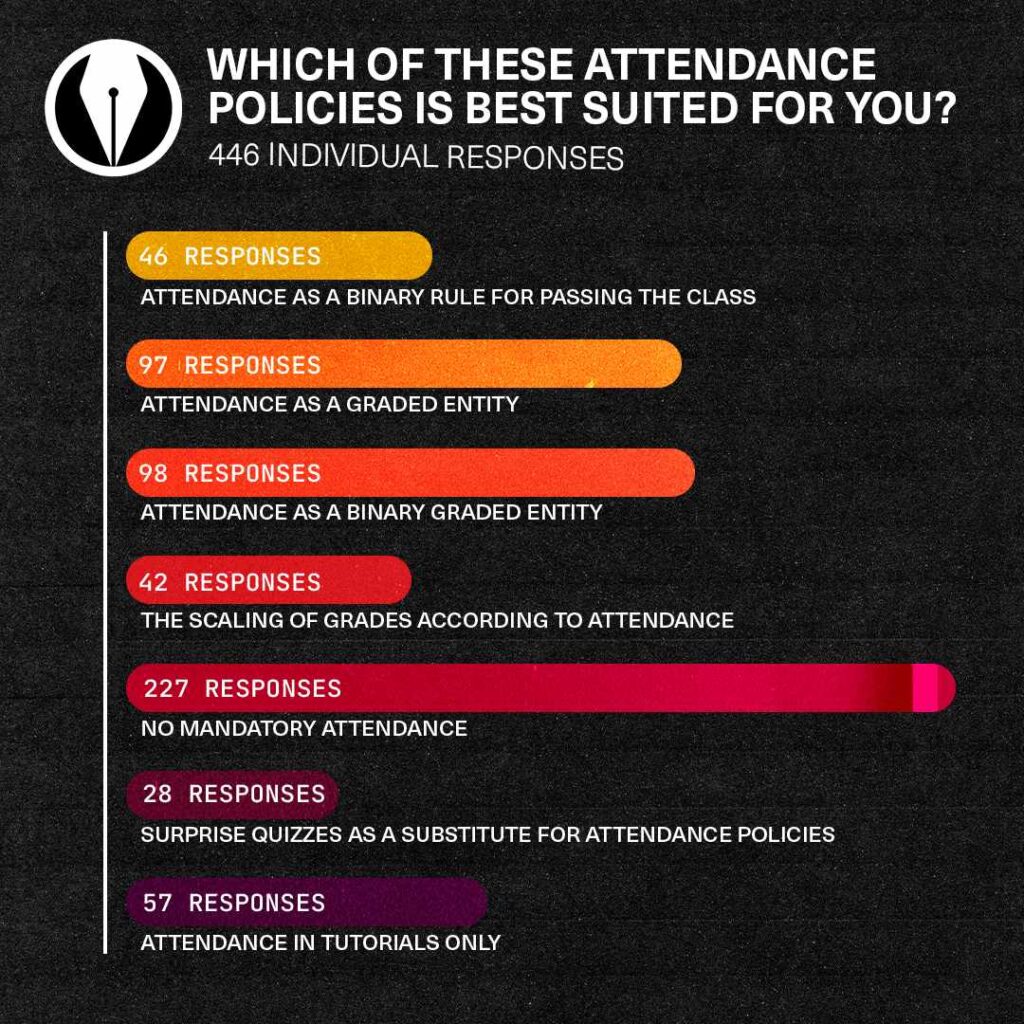

As the final question in our questionnaire, we asked both the professors and students what their ideal attendance policy would be: Two main approaches were highlighted.

1. Students are functional adults; it is their choice whether to come to class or not at the end of the day, and professors would rather not spend resources policing them. They also believe that forcing attendance does not change the student’s intent to learn, which is the real problem.

At the same time, both students and professors recognize that, in many cases, the lectures do not seem engaging enough to the student. Motivation drops, and attendance follows. Prof. Tapobrata Sarkar mentions that he overcame the issue of engagement in class by having an open discussion with his students about their teaching needs. He does not follow a compulsory attendance policy.

2. Incentive: Many professors set an attendance requirement to urge students to make the extra effort to remain in touch with the course. For example, Prof. Arijit Kundu acknowledges the variety of activities on campus. This is why he says he sets attendance criteria for UGs (“especially first-years”) so that they have an incentive to learn throughout the semester as opposed to cramming before exams.

Where,

Attendance as a binary rule for passing the class: You must attend a set percentage of classes to be eligible for giving major exams and passing the course

Attendance as a graded entity: Attending each class gives you a certain percentage of marks

Attendance as a binary graded entity: Attending a minimum number of classes would make you eligible for extra marks

The scaling of grades according to attendance: Attendance serves as multiplying factor to your course total

Among students, we also see a divided opinion. While 49.7% of the students do not want any attendance policy, 43% of the students do want attendance to hold weightage

To conclude, IITK’s unique position in providing freedom to professors to set their attendance policies has thrown up some interesting policies.

Education has long been an evolving landscape, and this continued evolution necessitates thoroughly examining these policies, largely driven by the insights derived from the professors’ perspectives. To quote Professor Manindra Agarwal, “It is clear that we will have to experiment with different methods of teaching as the traditional methods of teaching don’t seem to work anymore. We’ll have to try and find out what is working right.”

Written by: Mayur Agrawal, Likith Sai Jonna, Shruti Dalvi, Pranav Agarwal

Edited by: Zainab Fatima, Mohika Agarwal, Kunaal Gautam